This is the beginning of a series of articles, describing Paul Taylor’s journey in making a cheap and easy to make biochar kiln or oven for the small property and small farmer. This will eventually take me back to my origin with biochar in 2007, and stoves, ovens and kilns explored, understood and developed along the way.

The Kon-Tiki Deep Cone Kiln

July 4 2014, Ithaka Institute, Switzerland

A break through in the journey was my work with Hans-Peter Schmidt at the Ithaka Institute in Switzerland last July to commission a large cone kiln, which we dubbed the Kon-Tiki. Like some others (such as Kelpie Wilson of backyard biochar and Tom Miles) I had been exploring, and including in my presentations, the Japanese Cone Kiln (the Moki Kiln) since 2011, and so was glad to have an opportunity to see how far we could take it. The Kon-Tiki worked magnificently, and seemed destined to set a new trend and alternative for biochar making – confirmed now by the response around the world, resulting in many large Kon-Tikis being built.

See Recent Publications:

Video – Making Biochar in an Open Deep Cone Kiln

Article – Kon-Tiki – The democratization of biochar production – A Review

For me the Cone Kiln falls in a class that could be called Cavity Kilns or Top Lit Open Burn Kilns. In future articles I will distinguish these from other devices such as Retorts (example Double Barrel Retort), and microgasifiers (example TLUD or TopLit UpDraft). But first I would like to share why we called it the Kon-Tiki, and in the next post what happened on the Maiden Voyage.

These notes were written last July in the evenings, after the days run, in the guest quarters of the Ithaka Institute in Switzerland.

Thanks to the Ithaka Institute for hosting the work, and to the Biochar Journal for publishing it. Please visit these sites and support their work.

http://www.ithaka-institut.org/en

http://www.biochar-journal.org/en

Why we called it the Kon-Tiki

The Kon-Tiki is fashioned after a Japanese Cone Kiln.

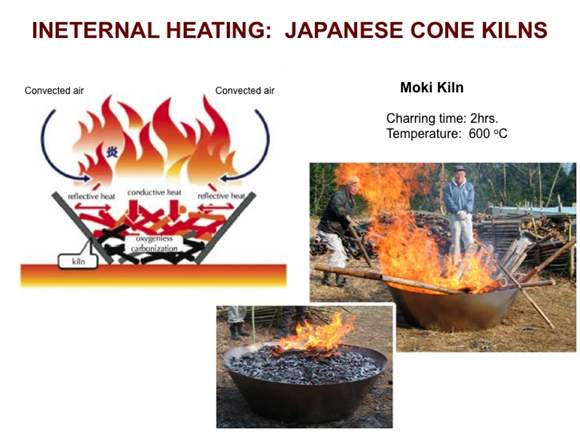

As pictured here, the Japanese Cone Kiln is typically a shallow cone with about 45osides. The illustration conveys that air is convected into the kiln to support combustion above the feedstock. Pyrolysis is supposed to be driven by radiant, reflected and conducted heat. Pyrolysis gases rise and are consumed in the flames resulting in clean combustion of the smoke. Char is preserved in a relatively oxygen free zone.

We hypothesized that traditional fire management practices, by Amazonian Indians, Australian aborigines and others, may have incorporated some principals of this contained-oxygen-limited pyrolysis of biomass. For example a semblance of the cone kiln could be created by felling and dragging trees into a circle and feeding a fire in the middle with more bush.

In commissioning the Cone Kiln we felt that we might be on a voyage of discovery to prove the possibility of this process by past cultures, similar to the Kon-Tiki Expedition to prove that Polynesians could have navigated the vast pacific in reed rafts.

Thus the Kiln acquired its name.

Kon-Tiki was a name of the Inca sun god, Viracocha, also Apu Qun Tiqsi Wiraqutra, or Con Tici Viracocha.

In Sanskrit the word for fire is Agni, a major deity in the Vedic Pantheon. Agni and fire have a broad spectrum of meaning, referring to the primordial light and life at the root of the universe; cosmic energy, or the “Fire of Space”; and “psychic energy,” the powers of the human mind and heart, particularly those manifesting in love, thought, and creativity. In general, fire is seen as a powerful transformative energy, a swift, subtle, connective force of high vibration.

Pyrolysis is an increasingly important process to cleanly convert waste materials into valuable end products. In bringing this process into cultural awareness through backyard and small-property biochar projects we are acknowledging the energy of fire, which has been typically repressed by our culture, and therefore has manifested in its dark destructive side, such as raging forest fires, nuclear weapons and an increasingly pervasive cultural anger.

Agni Yoga is predicated on a belief of construction of a New Era, and the battle to create conditions under which construction is possible. Unlike many traditional approaches to the mastery of subtle energies, Agni Yoga insists that mastery must take place within the context of contemporary secular life by action for the Common Good, creative work that helps build a new era based on knowledge that is both scientific and spiritual.

Part of the ritual of Agnihotra is to honor fire, and its connection with the sun, in a shallow inverse pyramid shaped hearth, similar to a shallow cone kiln. Thus Kon-Tiki Viracocha, sungod, connects with Agni, god of fire, heart and science, and the project to reinvent fire in our culture – a project close to my heart since I collected my first Agnihotra pyramid kiln in 1981 in India. Its why I was happy to have Peter Hirst’s wonderful Chapter 4 in The Biochar Revolution, “From Black Smith to Biochar: The Essence of Community.”

You can download this chapter of the Biochar Community for free by clicking through this link

Stay tuned for the next post, coming soon, Maiden Voyage of the Kon-Tiki Kiln

Leave A Comment